What It Feels Like: Lessons from a Startup that Almost Made It

(aka A personal journey through ambition, bias, and building something that mattered — until it didn’t)

For me, starting a company was brutal. This post highlights the moments that felt like breakthroughs and the setbacks that stung. Interwoven throughout are a few practical insights for other founders to consider, drawn from my successes and my failures, and the piece concludes with a few reflection prompts designed to help you anticipate pitfalls, protect yourself and your team, and make smarter decisions.

Getting Started

I was what some people (not me, but that’s a different story) might call a late bloomer. I went to community college. I took the path less traveled and moved to France right after undergrad to briefly live the strange, under‑the‑radar life of a young ex‑pat teaching English to French executives in large companies. I returned to the U.S. and interned at a public access TV station where I learned how to coil wires and produce live news. Eventually, I ended up in strategic communications, design, and research with an MA in Media Studies from the New School.

Pro Tip: Don’t underestimate the value of eclectic early experiences — they build resilience and perspective you’ll use in unexpected ways.

By 2014, when I took the plunge into starting my own business, I had found a fascinating niche, moving deeper and deeper into the science of movement building in complex social systems. My first thought was to create a nonprofit fellowship program that would bring cohorts of problem solvers together to work on solving complex problems, inspired by how storytelling was such a powerful force in philanthropy. Storytelling was, in many ways, the only tool people in need had to advocate for themselves. I wanted to help them tell their stories more powerfully so they could be heard. But we needed a unique capability to help make this happen, and I knew the answer lay in technology.

I dug deeper and deeper into this question, until I discovered a new way to apply the power of computing to mixed‑methods research to strengthen group decision making in a way that scaled the analysis of human insight and the power of human collaboration. The applications felt endless.

Pro Tip: Deep exploration of the problem space can reveal unique opportunities that are not obvious at first glance.

Launching a Company

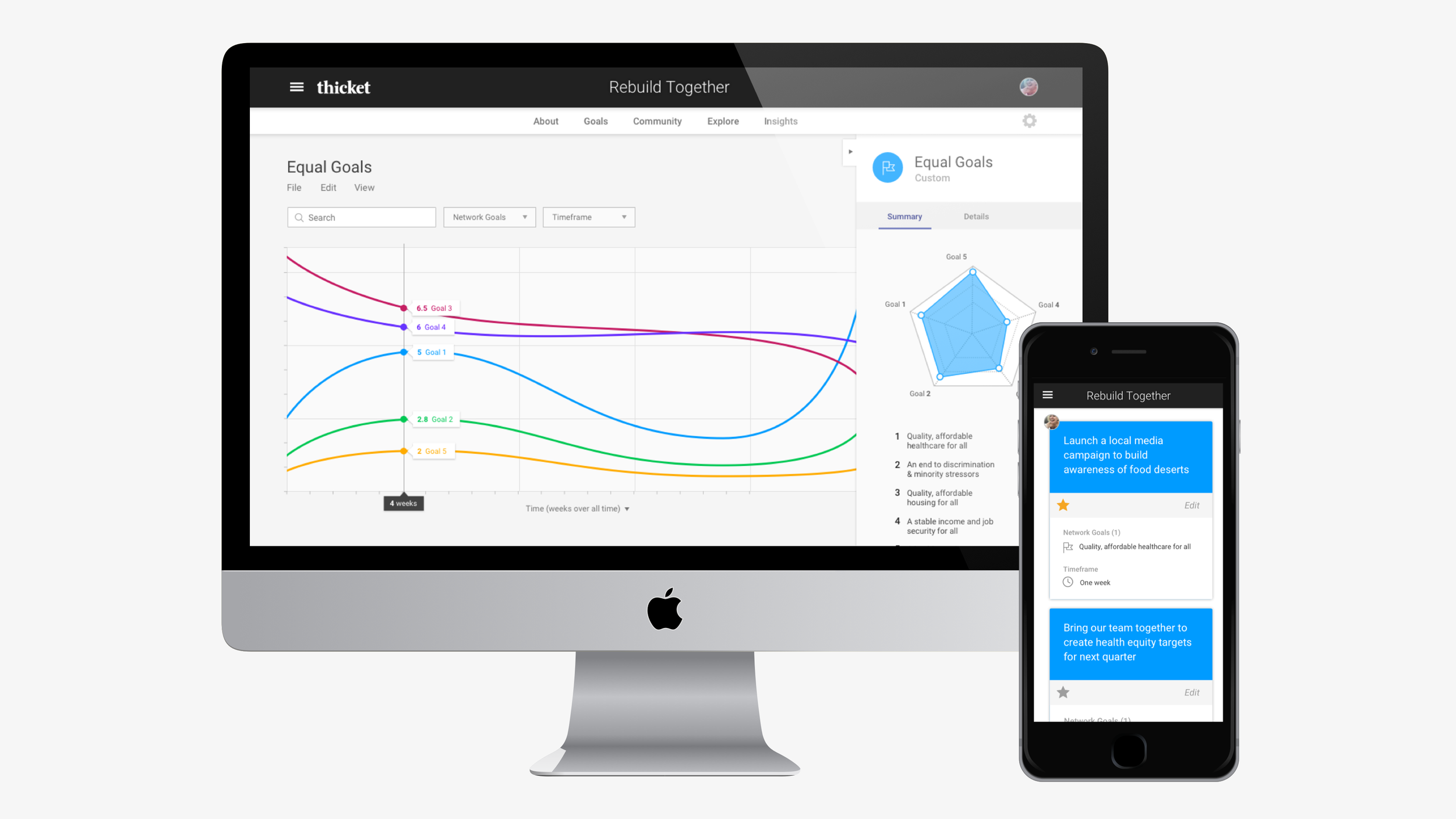

I saw the opportunity to create a company with a structure similar to Google, where employees could create their own solutions using the remarkable capabilities our core technology enabled. At some point, I had walked by the vine‑wrapped headquarters of Palantir in Palo Alto, which looked from the outside like a beautiful, calm, and peaceful place to work — and I thought: our core technology could be just as powerful, but serve a very different client base. One morning in late 2013, I woke up with the perfect name resounding in my head: Thicket. In January 2014, I launched Thicket Labs, a company that was to become variously described as a data‑driven design lab, a collaborative AI company, and a civic‑tech startup.

Pro Tip: Inspiration can strike anywhere. A name, a vision, a metaphor can become your compass.

Our team was diverse from the start by design, and our clients and partners were at respected institutions and companies in New York and around the world. By 2019, my humble startup had strengthened research and learning programs aimed at helping millions of people around the world, been featured at SXSW Interactive two years running, and been featured in USA Today for a study commissioned by Google alongside the TV‑research giant the Annenberg Institute. We had achieved sustainable operations at the $15k project level while also selling with a healthy profit margin at the $350k project level.

It felt like we should have arrived. But along the way, we also were constantly running out of funding, were on an endless hunt for clients, had a significant talent partnership fall apart at a critical moment, never found an accountant who understood our needs, could only barely sustain our operations, and, despite hitting all the traction goals supposedly needed for a Series A round, never got outside investors to back us.

Pro Tip: Traction and metrics are important, but they don’t guarantee investment or scaling. According to a 2022 poll of almost 500 founders, 47% of startup failures were due to lack of financing and 44% due to running out of cash. (CNBC, 2023)

On Shaky Ground

I will freely admit that I wasn’t the best founder. I had to be convinced by my team to change my title from Principal to CEO. I passed up easy wins for the long‑term vision. Sometimes, I was an annoying influence on the product design process. Sometimes I messed up negotiations or didn’t move fast enough to grasp opportunities in front of us. I felt depressed, scared, and intimidated every day. Towards the end, I started thinking about how to hire a CEO to replace me who could do better. Sometimes I thought it should be a white man who could access the kinds of deals that were beyond my reach. In practice, I approached a brilliant Black woman working for a global tech consultancy about how she might lead the team. She was hesitant about the possibility and never got back to me.

Pro Tip: Self‑awareness matters. Recognise your strengths and your limitations. Find complementary leadership or mentorship early.

I was also sexually harassed by a potential advisor, client, or investor every few months and spoken to dismissively on a weekly, sometimes daily basis. I was scoffed out of all sorts of meetings and directly insulted for setting my ambitions too high (“How dare you compare your company’s business model to Google?” “You aren’t building a SaaS company, despite all the glaring evidence to the contrary.”). I was demoralized by seeing countless other founders I respected be trodden underfoot by angel investors who seemed to just want to see their mini‑mes succeed. By now, I’m sure you have realized that I was a non‑white, non‑male founder. Demographically, I am a South Asian woman. I come from privilege in many ways. There is no way I could have continued to grow this business as long as I did without that privilege. But in certain circumstances, that privilege only went so far.

Another South Asian woman about my age working for a Silicon Valley‑based venture fund took a meeting with me only to shame me for comparing my business model to Google. She told me I was severely out of touch with reality for thinking it was appropriate to do so. It was less than two years later that Google hired us for our technology platform and research chops. The then‑CTO of the largest TV ratings company in the world, also South Asian, told me I should focus on politics despite the fact that we were in the midst of conducting a ratings study that any of their clients could have used.

An imposing and respected veteran scheduled a coffee with me under the guise of being a potential advisor at a coffee shop just below his apartment. He wouldn’t stop asking me to go upstairs until I cut the coffee short after he refused to have a serious conversation about my company. A partner at a Palo Alto-based immigrant VC fund told me I was not building the company I thought I was building, as if, just by saying the words, he would be right.

Pro Tip: Bias and dismissiveness are real. Persistence plus evidence can help you prove your model, but you may still face gatekeeping you can’t control. For example, companies with at least one female founder captured 27.8% of total U.S. VC deal value in 2023 — still far from parity. (PitchBook, 2024)

A Fraught System

Day in, day out, I found myself in pitch mode, explaining or defending my reasons for starting a company and for thinking it was a good idea and would make decision making more inclusive, trustworthy, and effective. The continuous self-promotion took its toll on my confidence. Over time, I learned to see myself as never smart enough, focused enough, or generous enough to win support from people who I thought should have been our supporters . In those and many other moments, I felt weak, untrustworthy, and a bad communicator. At the same time, our results for all of our paying clients proved that all of our assumptions, design choices, and implementation strategies were valid. The steadily increasing wins sustained my positive energy and outlook in the face of growing imposter syndrome.

The sexual harassment was largely (but certainly not entirely) from men of varying ages but a depressingly consistent audacity. I was constantly on my guard, trying to figure out where our next paycheck would come from, how we could stop having to do free work, how to increase the amount we could charge for our services, and how to build a self‑sustaining operation, all the while trying to avoid putting myself in unsafe or uncomfortable situations. The cold comfort of that last part is that I had been facing these situations well before I started a company, so that wasn’t new. Talking about it publicly was never something I felt comfortable doing until this last year.

And it wasn’t just sexual harrassment. I felt my powerlessness in nearly every arena of business. One accountant refused to work with me when I tried to hire him in my first year. A former employee violated the NDA they signed, and when I sent a cease and desist, replied with a picture of a cat to show me just how little they thought of me by then. Would they have had the courage (audacity) to respond that way to a white male boss? I had to wonder. I had wonderful legal advisors for a time, until I went the route of a “respected” larger firm that hit me with an astronomical bill for a tiny amount of work. (Ultimately, we settled for a fraction of the bill.) All of this left me with the indelible understanding that not only was I not cut out to lead, but everyone else knew it too.

I would constantly think about how to pay back my small group of investors, all of whom were related to me. I spent years trying to figure out if filing for bankruptcy would be necessary, or even possible, since personal liability was built in to every agreement I signed. I felt trapped in a way that I had never felt before. I also had the vague sense that I was, if not a white collar criminal, something just as bad in relation to my investors. That period of time started mid-2014 and lasted until mid-2018, just about four years. I was not able to pay off the debts I built up during that time until 2022.

I also felt the burden of being the boss. Being sexually harassed, I worried about my team all the time. I found it uncomfortable to make decisions about the way our team dressed and worked and talked, because I myself had been unable to stave off unwelcome attention and accusations of lack of professionalism, and I also didn’t want to police the way people dressed. But I never forgot that it was my responsibility to ensure the safety of my team, and I took steps when I had to, despite facing high barriers when it came to basic respect, at times from my own team. I felt the weight of not being able to generate the income for the company to succeed and often didn’t feel able to question others’ lack of belief in me.

Pro Tip: Protecting your personal safety and your team’s safety matters as much as any product roadmap. No startup wins if its foundation is unsafe. 72% of founders report that entrepreneurship has impacted their mental health, but 77% don’t get professional help. 81% of founders are not really open about their stress, fears, and challenges. (Startup Snapshot, 2023)

Financial Fragility

I was also under enormous financial pressure. I had sunk my own capital in the start, to supplement client funding, but I soon transitioned to operating primarily through friends and family funding. I had periods of three to six months where we had enough money in the bank to keep operating, but also three- to six‑month periods where I had to ask (read: beg) for money to keep going — money to make payroll, money that I could pay back most of the time but occasionally could not. I was constantly ashamed and embarrassed.

I knew that at least one of my investors thought I was paying my team too much, but I also knew that I was paying well below what my individual employees could command on the open market. This was largely because our model was built on pay equity. Our equity principle was that no matter how large the company grew, no one would ever make less than a fifth of anyone else’s salary — including my own. In practice, we only ever instituted three pay tiers, and I as the CEO made less than anyone else because I was putting every dollar I could back into the company — even racking up debt when I couldn’t.

Glimpses of Success

During those four years, we got close. We were hitting our marks, closing the gap between our monthly burn rate and our monthly revenue, building consistent successes, and delivering a product that exceeded performance benchmarks and consistently won high customer satisfaction and exceptional user‑experience ratings. We had amazing advisors and fellowship opportunities. We worked across a breadth of industries, bringing that original vision of endless applications to detailed and diligent life.

We even had glimpses of what it would look like to succeed. We were invited to join fellowships at NASA, Personal Democracy Forum, and SOCAP and to present at conferences like SXSW and the American Evaluation Association. We were offered free office space just north of Madison Square Park by the global technology consultancy Thoughtworks. Our team was bold and innovative, and opportunities often emerged organically from being situated in the heart of New York City.

Pro Tip: Celebrate the wins — each one is a signpost that you’re on the right track, even if the destination changes.

Accepting Failure — Almost

But eventually, I stopped believing that success was possible. I stopped believing that our services were valuable. I didn’t trust the sales to come through. Too many people said no. Too many people tried to take advantage of us — and a few succeeded. Too many decision‑makers said they wanted inclusive decision‑making but changed their minds at the last second. Too many of our clients had their own funding cut while we were working with them.

I didn’t believe that I was going to succeed in a world where not only could I not convince the gatekeepers despite my best efforts, but my brilliant clients couldn’t either. And we had been hired by brilliant people, ranging from products of elite schools and training around the world to the most extreme outsiders who had made their way in through sheer personal effort. Our backers tended to be extremely well‑intentioned thought leaders who believed that research and innovation were necessary building blocks of a flourishing economy. But the clients who wanted to hire us again repeatedly pulled us into ultimately unsuccessful proposals. Our shared point of view was represented but had limited influence.

One Last Attempt

Eventually, I had to start working elsewhere part‑time and then full‑time to make ends meet, but I kept working on reviving the company. In 2020, we pitched investors and got some interest, which once again fizzled out in follow‑up meetings. I tried reorganizing the company as a cooperative, but moving away from its origins as a startup proved too difficult to surmount. After a couple of years away, I gave it one more lonely attempt as a solo founder, spurred by my frustration at seeing the hype cycle at work around emerging generative AI products in early 2023, combined with a few acquisitions happening in social intelligence products.

But it was too late by then: During my most financially insolvent period, I couldn’t afford to pay for the company’s Google Workspace account. As a result, I lost most of our records and with it, our institutional history. I still had our codebase but couldn’t bring myself to invest in bringing our platform fully back online again, so I didn’t have a full demo for prospective clients or investors. Eventually, I accepted that it was too late for my company to succeed and finally took the necessary steps to shut it down.

Pro Tip: Accepting that external factors — timing, resources, ecosystem — are beyond your control is not defeat. If it feels like failure, it might be. But remember that failure is also sometimes outside of your control.

Finding Meaning in a Closed Innovation System

In the end, my story is just the story of a company and a culture that tried and failed to exist. AI is far from intrinsically evil. But I have soured on it because I see it being wielded today in indefensible ways, and my efforts to offer a counterpoint did not succeed. I see AI and innovation as synonymous with villainous figures like Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, running villainous companies like Open AI and Palentir that have no interest in steering AI in a collaborative or democratic direction, and a venture capital funding community that operates more like the information wing of global fascist regimes than a storied engine of industry bringing opportunity to the world. I would love for AI companies that value transparency, sustainability, and democratic decision making win out, but that’s not what I’m seeing happening these days. (On that note, if you’re an ethical and eco-friendly AI company interested in partnering with me, please reach out to connect.)

I took some measure of pride in winning the contract with Google, where we were hired to measure the impact of a talent‑pipeline program to attract more women and BIPOC people into the field of computer science. But the reality is that a few years later, they stopped funding the program as soon as it was clear that it was working. According to one executive let go from Google as well as public reports, this was largely due to internal white male rage. This fear of those in power losing power defines the culture of the tech industry, who is allowed to succeed in it, and who isn’t. I miss working with technology and with technologists, but I don’t miss working within the technology industry.

At the same time, I don’t want to fall into the trap of myopia, framing the tech industry as somehow worse than every other industry. Just like at Google, two of our healthcare clients, funded by public agencies in two different countries, had their funding cut despite being able to demonstrate that they were delivering significant positive outcomes and impact at a systemic level to millions of people.

In some ways, this shouldn’t have been a surprise to me. My first job in strategic communications involved being physically shoved and threatened by the nineteen-year-old son of my boss in an otherwise empty office. Ironically, a large portion of our work was in youth violence prevention. A few years later, I worked at a startup largely committed to social cause clients and left-leaning political campaigns that was acquired by one of the largest advertising holding companies in the world during my time there. This was the first company where I became aware that women and BIPOCs were being systematically underpaid and underpromoted. At the time, it seemed from the outside that my departure and that of others like me forced this company to make positive changes. Given the state of the world today, I have a hard time believing that my departure meant anything to them.

Question: Purpose and impact can be more sustainable motivators than growth alone, but in the end, does it really matter?

I have started a new company, but it’s really just the legal entity through which I freelance. It’s always possible it could grow into something more, but I’ve learned a lot of lessons, one of which is that I am not interested in taking on venture capital again, and two, I don’t feel capable of being responsible for other people’s safety and wellbeing. I carried the weight of taking and spending other people’s money with me for years, and have now paid off my debts and repaid the investors who wanted to be repaid.

My present‑day goals are crystal clear: fight for justice and accountability, be financially solvent, prioritize my passion for music and art, do interesting, worthwhile, and creative work, and do what I can to decrease the wealth gap and increase diversity, equity, and inclusion in all parts of society — and by extension, contribute to a kinder, safer, healthier world for all. Even if it is a mirage in my lifetime, this mission deserves to exist in the multiverse and beyond.

Pro Tip: Define your values clearly. They will guide the next chapter of your career and keep you aligned with what truly matters.

Founder Lessons & Reflection Prompts

Reflecting on the journey of Thicket Labs, several lessons stand out, both practical and personal. These aren’t just cautionary tales; they’re prompts to guide founders in navigating the highs, the lows, and everything in between. Use them to reflect, anticipate challenges, and equip yourself for the messy, rewarding, and human journey of building something meaningful.

1. Embrace the full spectrum of experience.

Takeaway: Eclectic backgrounds, unusual career paths, and “late bloomer” trajectories build resilience and perspective.

Prompt: What unconventional experiences have shaped you, and how can you leverage them in your startup?

2. Explore deeply before committing.

Takeaway: Understanding the problem space and testing assumptions will uncover unique opportunities.

Prompt: Which part of your business or product can benefit from deeper investigation before you scale?

3. Protect your safety and your team.

Takeaway: Harassment, discrimination, and bias exist in every ecosystem. Prioritize clear boundaries, reporting structures, and mental health resources.

Prompt: How are you safeguarding your well-being and that of your team? Who can you turn to for support and accountability?

Context: 72% of founders report mental health impacts from entrepreneurship, including anxiety (37%) and burnout (36%) (Startup Snapshot/Feld, 2023).

4. Finance is both foundation and stressor.

Takeaway: Cash flow, funding, and pay equity are constant pressures. Transparent communication and careful planning are essential.

Prompt: How will you structure funding, pay equity, and cash-flow safeguards so your team can thrive without constant uncertainty?

5. Gatekeepers aren’t always rational or fair.

Takeaway: Bias and dismissal will happen, and even evidence-based successes may not convince investors. Persistence matters, but know when to pivot or walk away.

Prompt: Which feedback should you incorporate, and which gatekeepers’ judgments should you set aside?

Context: Women-founded companies received only 27.8% of U.S. VC deal value in 2023 (PitchBook, 2024).

6. Celebrate wins, no matter how small.

Takeaway: Each milestone, whether it’s conferences, fellowships, contracts, or client successes, signals progress and proves that your vision resonates.

Prompt: What recent successes can you pause to celebrate, and what lessons do they teach you?

7. Define values clearly and live by them.

Takeaway: Your principles will guide decisions, shape culture, and sustain motivation through the hardest moments.

Prompt: What are your non-negotiable values, and how do they show up in your day-to-day decisions?

8. Know when to pivot and when to let go.

Takeaway: Acceptance of external factors — timing, resources, ecosystem dynamics — does not equal defeat.

Prompt: Are there areas of your venture where acceptance and recalibration would create space for new opportunities?

9. Protect your mental health as vigilantly as your business.

Takeaway: Entrepreneurship will test you in unexpected ways; ongoing reflection, support systems, and self-care are not optional.

Prompt: Which practices or routines can you integrate today to safeguard your mental health over the long haul?

I hope these reflections and prompts help you navigate your own path, whatever success ends up meaning for you.

Authorial Attribution

All narrative, reflections, and personal insights in this post are my original work.

How to Cite This Article

Rights and permissions: This work is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Under this license, you are free to copy, redistribute, and adapt the material, even commercially, under the following terms:

Attribution — Please cite this work as follows: What It Feels Like: Lessons from a Startup that Almost Made It by Deepthi Welaratna v.1.0 2025. CC BY 4.0 [link: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/]

Adaptations — If you remix, transform, or build upon this work, the following disclaimer along with the attribution is required: “This is an adaptation of an original work by Deepthi Welaratna. Views and opinions expressed in the adaptation are the sole responsibility of the author(s) of the adaptation and are not endorsed by Deepthi Welaratna.”